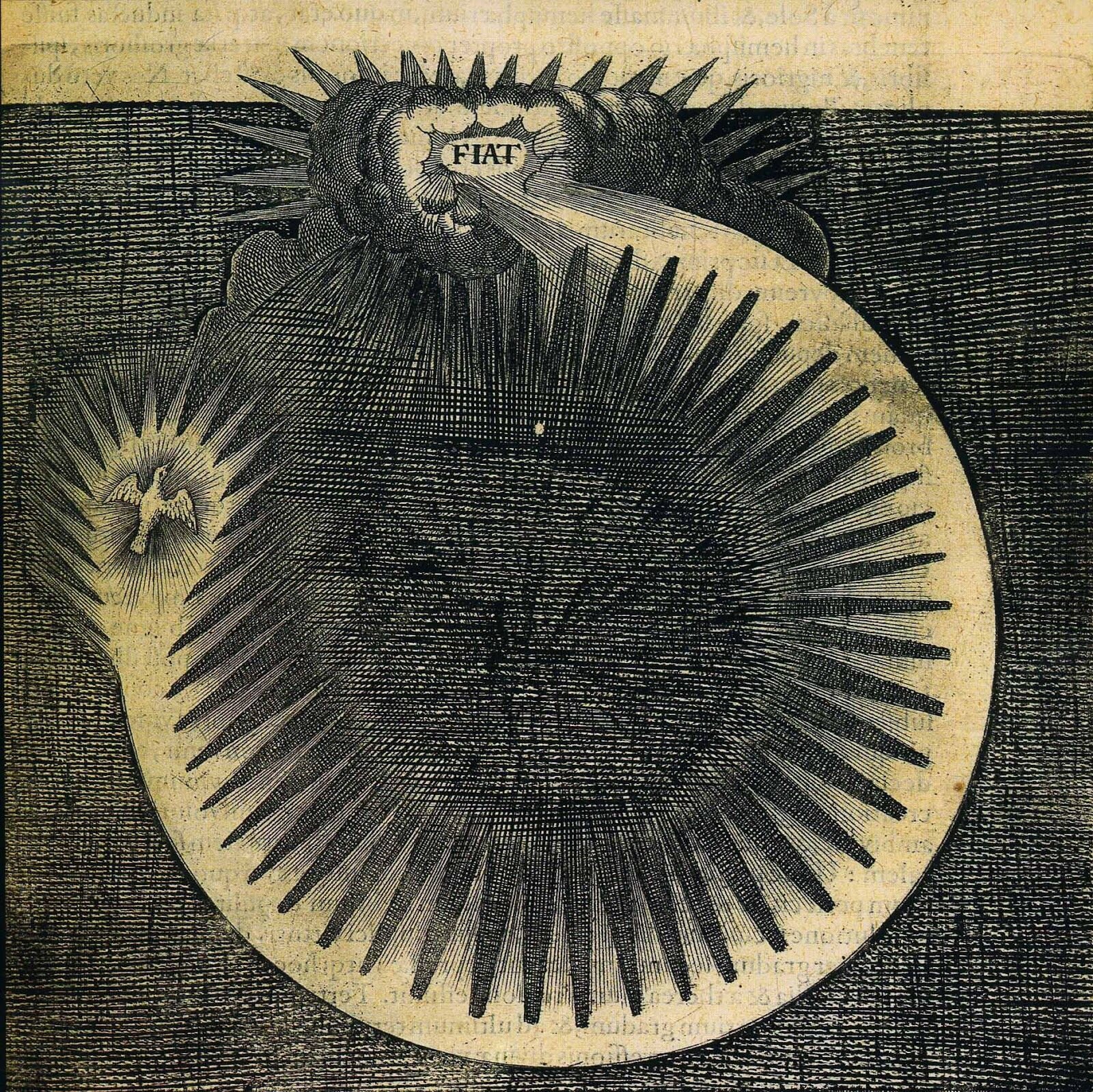

The Great Wheel: Spectre and Emanation

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

-- W.B. Yeats

Yeats wrote the lines above in 1919, in the midst of the global influenza pandemic, which claimed more than 50 million lives. The figure of the gyre, which continued to preoccupy Yeats for the remainder of his life and inspired A Vision, the poet’s most ambitious project, refers to a swirling vortex, a circular motion spiraling downward. For Yeats, the gyre, in its simultaneous movements of expansion and contraction, represented the ultimate symbol of history and the movement of the world and soul. As a refutation of the modern logic of progress, a preordained, irresistible march forward toward perfection, the symbol of the gyre returns us to the vision of the world held by the presocratics, Advaita Vedanta, and the so-called pagans, or pre-Christian Europeans. In the words of Empedocles: “there is no birth of all mortal things, nor any end in wretched death, but only a mixing and dissolution of mixtures.”

The world moves, ever circular, between concord and discord, the substances change forms and manifestations, but all return to the source and then once again emanate into the world. That which is implied and suggested merely bides its time. Empedocles again: “For already, sometime, I have been a boy and a girl, a shrub, a bird, and a silent fish in the sea.” Modernity, the logic of the arrow, in the words of John Moriarty is a gorgon-thing, a calcifying thing, which reduces fluidity to rigid stone. Forms in motion become static. As Yeats puts it we have slumbered through “twenty centuries of stony sleep.” We have all become like Michaengelo’s captives, entombed, imprisoned in stone. As Yeats writes in A Vision, the beginning of a new gyre, and the end of an old one, comes with great violence. The world shatters apart and all things become as fragments.

Do we have the strength of will and spirit to face the monstrous logic of the gyre? Or will we cling to our stones and monuments as they are blown into dust by the coming storm? Yes, the gyre is a thing of terror, for it sweeps away what has appeared solid and stable. And this does not merely refer to the outdated structures we resent and despise. We are more bound to the center than we may believe and as it loses its grip and flies apart, we find ourselves on shifting ground, which threatens to devour us. For Yeats, this movement comes through catastrophe: “the blood-dimmed tide is loosed.” We wade through rivers and oceans of blood. In his recent essay “A Storm Blown From Paradise,” Paul Kingsnorth aptly pairs Yeats’ gyre with Walter Benjamin, for whom it’s realization meant suicide in September of 1940. Benjamin’s haunting figure ‘the angel of history’ is tragically confronted with the ongoing catastrophe of progress. The future is obscured, the past is endless ruination. For those who see in this turmoil the coming birth of a new radiant dawn are likely to be shocked and horrified by Yeats’ slouching beast: “No more water, the fire next time.” The Second Coming will not be as the First.

The gyre, which is for Yeats the precise form of the movement of history and individual life, begins at a discrete point and widens progressively. At its apex, the moment of its furthest expansion, it begins to contract and spiral down. ‘The revolution,’ which is so ardently prayed for by the socialists and their enemies, shall not come. There will be no final victory, nor defeat. There is only the endless repetitive revolutions of the gyre, which are destined to grow, contract, and begin again in moments of discord and strife.

The gyre can be represented either singularly or as a double. In both cases, the meaning is the same: the lowest point is simultaneously the highest. As one force waxes, another wanes. Unsurprisingly, in A Vision, Yeats conceptualizes the gyre in terms of the phases of the moon. Each victory is in fact a defeat, and vice versa, for no force may reach its highest point without bringing about the eventual triumph of its opposite. This also means, of course, that nothing may be utterly removed from the totality of the world, for even as one gyre approaches its zero limit, its constant motion requires that it does not vanish but begins to expand again. Culmination and dissolution are one and the same. While the rate of expansion within the gyre can increase or decrease, the movement cannot be altered. The entirety of the realm of human action occurs within these minute increases or decreases in the speed of the spiral.

One of Yeats most succinct explanations of the gyre can be found in a lengthy note included in the publication of “The Second Coming”:

the end of an age, which always receives the revelation of the character of the next age, is represented by the coming of one gyre to its place of greatest expansion and of the other to that of its greatest contraction. At the present moment the life gyre is sweeping outward, unlike that before the birth of Christ which was narrowing, and has almost reached its greatest expansion. The revelation which approaches will however take its character from the contrary movement of the interior gyre. All our scientific, democratic, fact-accumulating, heterogeneous civilization belongs to the outward gyre and prepares not the continuance of itself but the revelation as in a lightning flash, though in a flash that will strike only in one place, and will for a time be constantly repeated, of the civilization that must slowly take its place.

The qualities that make up the character of a historical age, in other words, do not lead to the fulfillment of those qualities, but rather to their emptying and retraction. The modern world is particularly hostile to this notion. Who could imagine that the “progress” made over hundreds of years of struggle and advancement would not lead toward achievement, to culmination, to an opening of even greater and more glorious horizons? We see vividly now, that progress does nothing of the sort. It does not lead us further into the future but ultimately drags us back down to the depths. At the historical moment of fruition, the forces recede and their opposing forces come to the ascendant. The fundamental error of modernity is in denying this inviolable law. In this world, we move from ruin to ruin.

In the figure of the double gyre, which Yeats ultimately uses more often than the singular, we can especially perceive the significance of the latent or that which exists in potential. As we have noted above, one force can never be extinguished from the world, but merely recedes as another advances. But since the height of its recession signals its coming expansion, we must see that forces are always preparing the way for their return, even as they dwindle. A retreat is always a gathering of strength. That which is inchoate is perpetually waiting for its moment to burst forth into fullness. Thus the shadows we perceive are nothing less than forces growing in power, and that which stands before us resplendent in its strength and vigor is, in fact, already withered and decaying.

We’ve thought that we were always for the moment, for culmination. The thing we await is coming, there is no doubt about that. But it is not the thing we wanted, or thought we wanted. That which we have hoped and waited for turns out to be a rough beast indeed. And what it brings is not the fulfillment of our powers but their dereliction and darkness will drop again.

I, too, await

The hour of thy great wind of love and hate.

When shall the stars be blown about the sky,

Like the sparks blown out of a smithy, and die?

Surely thine hour has come, thy great wind blows,

Far-off, most secret, and inviolate Rose?

--W.B. Yeats

RAMON ELANI

Ramon Elani is an acausal, anti-modern, heathen poet and author. He holds a PhD in literature and philosophy. He lives with his family among mountains and rivers in Western New England. He follows the way of wyrd.